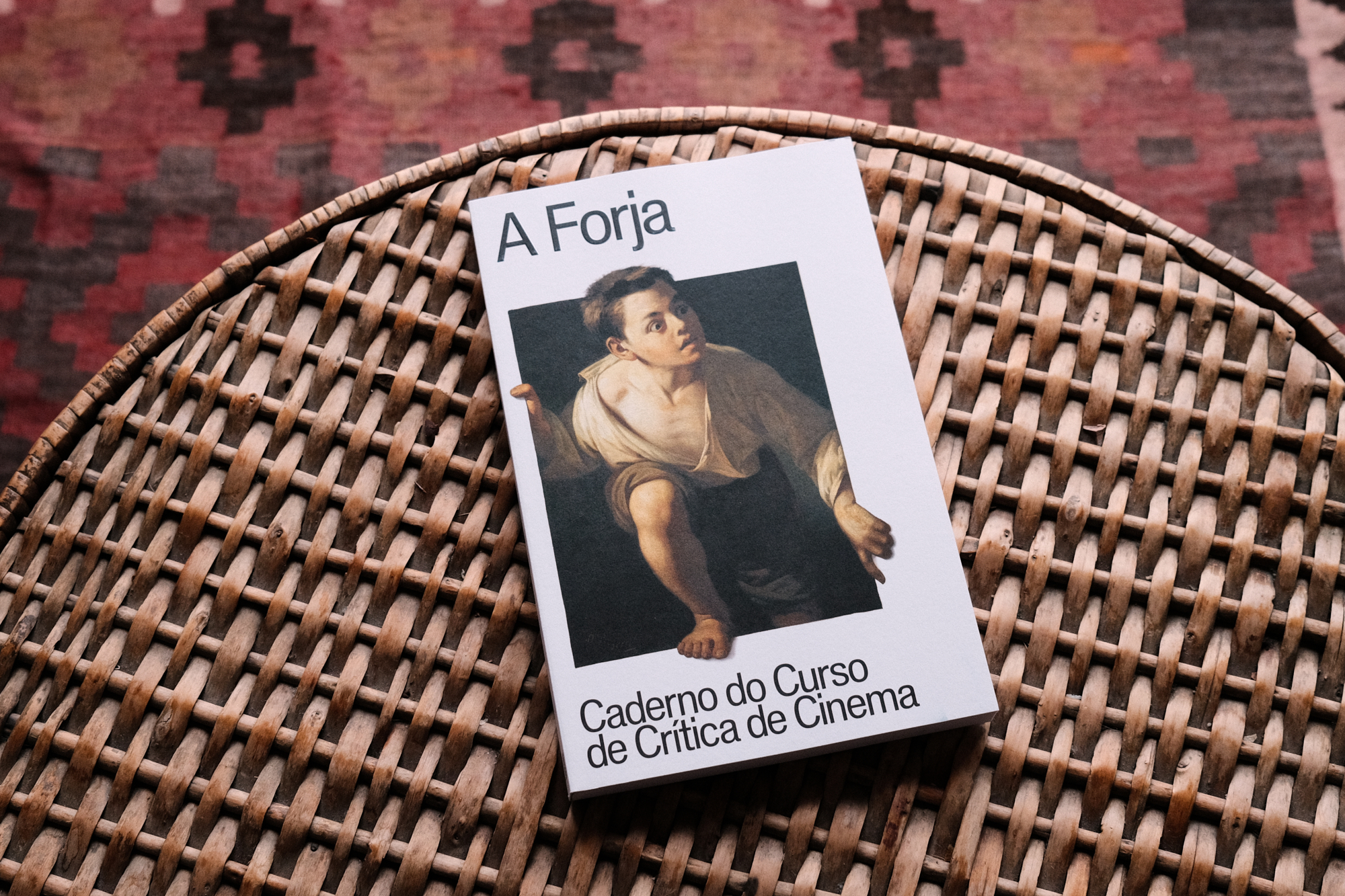

January 18, 2024 - A Forja

In 2023 I attended the Film Criticism Course “A Forja” (”The Forge”) with a group of 15 other people at Batalha Centro de Cinema. The course was very insightfull with different teachers from diverse areas such as Theatre, Literature, and Art. We were proposed to write two reviews, one about a film and another about a non-film piece of art. Regarding the film I wote about Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles”. Last week Batalha published a book with all the texts. You can read below my text about

“Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles”.

English

The Time of Jeanne Dielman

Chantal Akerman offers us to live three days in the life of Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig) and follow her daily routine almost uninterruptedly. In fact, what we feel when we watch the 3-hour and 14-minute Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) is that time is long and that Jeanne's actions are initially tedious. Compared to the editing pace and camera movements of today's cinema, Jeanne Dielman is a film devoid of gimmicks, which gives us time to analyse and reflect on everything we see, from the actions of the main character to all the elements in the frame, using the fixed shot.

Through the repetition of the same actions, the viewer is able to focus on the differences in their details from one day to the next, as well as their meaning. As Jeanne's psychological state deepens, her actions - which are initially careful and meticulous - begin to fall apart: the button that is left undone, the cutlery and shoe that fall out of her hands, the potatoes that are overcooked. The cherished ritualised routine that begins to break down signals that something is not right and that something might change.

The action takes place between a Tuesday and a Thursday. These are mid-week days. The weekend would bring something out of the ordinary, Friday would anticipate the weekend and Monday would still have traces of the two previous days. We are looking at three days that will be the typical day for this woman, a widow, and her son. The routine and actions are seen as a ritual, so that a false peace of mind is given and silences are hidden, in which there would be time for self-reflection and awareness of the protagonist's "self". Even when Jeanne and Sylvain (Jan Decorte) have dinner later, the latter suggests that they not take their usual evening stroll through the city that night. Jeanne agrees. Despite this agreement between the two, in the next sequence we see them leaving the flat. The walk through the city is not carried out for a playful reason, but rather to maintain a non-verbal routine pre-agreed between them. Not carrying out the walk would mean a drastic change in their routine. Although it may seem mundane, it could open up time for reflection, which is what the characters run away from in this film. Their bodies are not visible as they walk through the city, only the lights of lamps and passing cars. We hear their footsteps and they do not speak, almost as if they are not there and do not see what surrounds them.

All the actions Jeanne does are purely mechanical, aiming to maintain a structure that hides deep depression and anxiety, stemming from a personal frustration of not having a greater motivation to live. Six years after her husband's death, Dielman does not leave her social role of caring for her son and doing household chores.

Even when actions appeal to emotion, such as when we see her caring for a child or doing sex work, her gestures and expression are neutral, yet obsessive about always keeping objects and spaces organised and clean.

The director films the entirety of the household chores and conveys Jeanne's anxiety and frustration to the viewers, who initially identify with the mundane subject matter, but in a second instance begin to worry about the length and repetition of the chores. In this way, there is an identification of the viewer with Jeanne, as they share the same kind of emotions after the first hour of the film.

Time and spaces are indeed what drives a film that apparently doesn't have much action, but that intrigues us and leads us to observe every detail. Starting with Jeanne's title, name and address, followed by her almost total confinement to the interior space - even when it is outside, we are always presented with the same locations as well as the same actions, accentuated by the use of the same camera angle.

It is also important to note the importance of the use of off-field at various moments in the film. Instead of the camera following the action when it changes space, it remains still. In this way, the viewer is encouraged to use sound to decode what is happening in the space, but which they do not see.

At the end of the film comes a somewhat unexpected climax that functions as a release and result of Jeanne's frustration. We observe that there is an accumulation of actions that go outside the norm, and an exponential growth of Jeanne's anxiety in her silences, expressions and gestures. However, nothing would lead us to think that she could project her frustration on someone else, since she demonstrates herself throughout the three days as a defender and practitioner of the act of serving the other, whether it is her son, who does not participate in the household chores, the men she receives at home, with whom she has sex, or listening to the outbursts of the mother of the child she takes care of for a few hours.

Akerman's film comes at a time when the male predominated in the sphere of cinema. It comes to us today as a feminist statement on the role of women in cinema and society in 1975 and a reflection on the author and her history and personality.

The Time of Jeanne Dielman

Chantal Akerman offers us to live three days in the life of Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig) and follow her daily routine almost uninterruptedly. In fact, what we feel when we watch the 3-hour and 14-minute Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) is that time is long and that Jeanne's actions are initially tedious. Compared to the editing pace and camera movements of today's cinema, Jeanne Dielman is a film devoid of gimmicks, which gives us time to analyse and reflect on everything we see, from the actions of the main character to all the elements in the frame, using the fixed shot.

Through the repetition of the same actions, the viewer is able to focus on the differences in their details from one day to the next, as well as their meaning. As Jeanne's psychological state deepens, her actions - which are initially careful and meticulous - begin to fall apart: the button that is left undone, the cutlery and shoe that fall out of her hands, the potatoes that are overcooked. The cherished ritualised routine that begins to break down signals that something is not right and that something might change.

The action takes place between a Tuesday and a Thursday. These are mid-week days. The weekend would bring something out of the ordinary, Friday would anticipate the weekend and Monday would still have traces of the two previous days. We are looking at three days that will be the typical day for this woman, a widow, and her son. The routine and actions are seen as a ritual, so that a false peace of mind is given and silences are hidden, in which there would be time for self-reflection and awareness of the protagonist's "self". Even when Jeanne and Sylvain (Jan Decorte) have dinner later, the latter suggests that they not take their usual evening stroll through the city that night. Jeanne agrees. Despite this agreement between the two, in the next sequence we see them leaving the flat. The walk through the city is not carried out for a playful reason, but rather to maintain a non-verbal routine pre-agreed between them. Not carrying out the walk would mean a drastic change in their routine. Although it may seem mundane, it could open up time for reflection, which is what the characters run away from in this film. Their bodies are not visible as they walk through the city, only the lights of lamps and passing cars. We hear their footsteps and they do not speak, almost as if they are not there and do not see what surrounds them.

All the actions Jeanne does are purely mechanical, aiming to maintain a structure that hides deep depression and anxiety, stemming from a personal frustration of not having a greater motivation to live. Six years after her husband's death, Dielman does not leave her social role of caring for her son and doing household chores.

Even when actions appeal to emotion, such as when we see her caring for a child or doing sex work, her gestures and expression are neutral, yet obsessive about always keeping objects and spaces organised and clean.

The director films the entirety of the household chores and conveys Jeanne's anxiety and frustration to the viewers, who initially identify with the mundane subject matter, but in a second instance begin to worry about the length and repetition of the chores. In this way, there is an identification of the viewer with Jeanne, as they share the same kind of emotions after the first hour of the film.

Time and spaces are indeed what drives a film that apparently doesn't have much action, but that intrigues us and leads us to observe every detail. Starting with Jeanne's title, name and address, followed by her almost total confinement to the interior space - even when it is outside, we are always presented with the same locations as well as the same actions, accentuated by the use of the same camera angle.

It is also important to note the importance of the use of off-field at various moments in the film. Instead of the camera following the action when it changes space, it remains still. In this way, the viewer is encouraged to use sound to decode what is happening in the space, but which they do not see.

At the end of the film comes a somewhat unexpected climax that functions as a release and result of Jeanne's frustration. We observe that there is an accumulation of actions that go outside the norm, and an exponential growth of Jeanne's anxiety in her silences, expressions and gestures. However, nothing would lead us to think that she could project her frustration on someone else, since she demonstrates herself throughout the three days as a defender and practitioner of the act of serving the other, whether it is her son, who does not participate in the household chores, the men she receives at home, with whom she has sex, or listening to the outbursts of the mother of the child she takes care of for a few hours.

Akerman's film comes at a time when the male predominated in the sphere of cinema. It comes to us today as a feminist statement on the role of women in cinema and society in 1975 and a reflection on the author and her history and personality.

Portuguese

O Tempo de Jeanne Dielman

Chantal Akerman propõe-nos viver três dias na vida de Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig) e acompanhar a sua rotina diária de forma quase ininterrupta. De facto, aquilo que sentimos ao ver Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles1, de três horas e 14 minutos, é que o tempo é longo e que inicialmente as ações de Jeanne são entediantes. Fazendo uma comparação com o ritmo de montagem e os movimentos de câmara do cinema atual, Jeanne Dielman é um filme desprovido de artifícios, o que faz com que tenhamos tempo para analisar e refletir sobre tudo o que vemos, desde as ações da personagem principal até todos os elementos no enquadramento, mostrados recorrendo ao plano fixo.

Através da repetição das mesmas ações, o espectador consegue focar-se nas diferenças dos detalhes das mesmas, que se alteram de um dia para o outro, assim como no seu significado. À medida que o estado psicológico de Jeanne se adensa, as suas ações — que inicialmente são cuidadosas e meticulosas — começam a desmoronar-se: o botão que fica por apertar, o talher e o sapato que lhe caem das mãos, as batatas que ficam demasiado cozidas. A rotina ritualista que tanto é estimada, e que começa a falhar, indicia que algo não está bem e que algo poderá vir a mudar.

A ação decorre entre uma terça-feira e uma quinta-feira. São dias a meio da semana. O fim de semana traria algo fora da rotina, a sexta-feira anteciparia o fim de semana e a segunda-feira ainda teria réstias dos dois dias anteriores. Estamos perante três dias que serão o dia típico desta mulher, viúva, e do seu filho. A rotina e as ações são encaradas como um ritual, para que seja dada uma falsa paz de espírito e se escondam silêncios em que haveria tempo para autorreflexão e consciência do “eu” da protagonista. Mesmo quando Jeanne e Sylvain (Jan Decorte) jantam mais tarde, o segundo sugere que naquela noite não realizem o seu passeio habitual noturno pela cidade. Jeanne concorda. Apesar dessa concordância entre ambos, na sequência seguinte vemo-los a saírem do apartamento. O passeio pela cidade não é realizado por uma razão lúdica, mas sim para manter uma rotina não verbal pré-acordada entre ambos. O facto de não realizarem o passeio significaria uma drástica mudança na rotina dos dois. Embora pareça algo mundano, poderia abrir espaço temporal para a reflexão, que é daquilo que as personagens fogem neste filme. Os seus corpos não são visíveis enquanto passeiam pela cidade, apenas as luzes dos candeeiros e dos carros que passam. Ouvimos os seus passos e não se falam, quase como se não estivessem lá e não vissem aquilo que os rodeia.

Todas as ações que Jeanne faz são puramente mecânicas, com o objetivo de manter uma estrutura que esconde depressão e ansiedade profundas, advindas de uma frustração pessoal de não ter uma motivação maior para viver. Seis anos volvidos da morte do seu marido, Dielman não sai do seu papel social de cuidado, do filho e das tarefas domésticas. Mesmo quando as ações apelam à emoção, como quando a vemos a cuidar duma criança ou a fazer trabalho sexual, os seus gestos e a sua expressão são neutros, no entanto obsessivos por manter sempre os objetos e os espaços organizados e limpos.

A realizadora filma a totalidade das tarefas domésticas e transporta a ansiedade e frustração de Jeanne para os espectadores, que inicialmente se identificam pelo tema mundano, mas numa segunda instância começam a inquietar-se com a duração e repetição dos mesmos. Desta forma, existe uma identificação do espectador com Jeanne, uma vez que partilham o mesmo tipo de emoções após a primeira hora do filme.

O tempo e os espaços são de facto aquilo que move um filme que aparentemente não tem muita ação, mas que nos intriga e conduz a observar todos os detalhes. A começar pelo título, nome e morada de Jeanne, seguidos pelo seu confinamento quase total ao espaço interior — mesmo quando este é exterior — , a obra apresenta-nos sempre os mesmos locais assim como as mesmas ações, algo que é acentuado pela utilização do mesmo ângulo de câmara.

Será também importante fazer notar a importância da utilização do fora de campo em vários momentos do filme. Ao invés da câmara seguir a ação quando ela muda de espaço, permanece imóvel. Desta forma o espectador é incentivado a utilizar o som para descodificar aquilo que decorre no espaço, mas que não vê.

No final do filme surge um clímax algo inesperado que funciona como libertação e resultado da frustração de Jeanne. Observamos que existe um acumular de ações que saem da norma, e um crescimento exponencial da ansiedade de Jeanne nos seus silêncios, expressões e gestos. No entanto, nada nos levaria a pensar que poderia projetar a sua frustração noutra pessoa, uma vez que se demonstra ao longo dos três dias como defensora e praticante do ato de servir o outro, quer seja o seu filho, que nada participa nas tarefas domésticas, os homens que recebe em casa, com os quais tem sexo, ou até a mãe do filho de quem cuida por umas horas, cujos desabafos costuma ouvir.

O filme de Akerman surge numa época em que o masculino predominava na esfera do cinema. Chega-nos aos dias de hoje como uma afirmação feminista sobre o papel da mulher no cinema e na sociedade de 1975, e uma reflexão sobre a autora e a sua história e personalidade.

O Tempo de Jeanne Dielman

Chantal Akerman propõe-nos viver três dias na vida de Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig) e acompanhar a sua rotina diária de forma quase ininterrupta. De facto, aquilo que sentimos ao ver Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles1, de três horas e 14 minutos, é que o tempo é longo e que inicialmente as ações de Jeanne são entediantes. Fazendo uma comparação com o ritmo de montagem e os movimentos de câmara do cinema atual, Jeanne Dielman é um filme desprovido de artifícios, o que faz com que tenhamos tempo para analisar e refletir sobre tudo o que vemos, desde as ações da personagem principal até todos os elementos no enquadramento, mostrados recorrendo ao plano fixo.

Através da repetição das mesmas ações, o espectador consegue focar-se nas diferenças dos detalhes das mesmas, que se alteram de um dia para o outro, assim como no seu significado. À medida que o estado psicológico de Jeanne se adensa, as suas ações — que inicialmente são cuidadosas e meticulosas — começam a desmoronar-se: o botão que fica por apertar, o talher e o sapato que lhe caem das mãos, as batatas que ficam demasiado cozidas. A rotina ritualista que tanto é estimada, e que começa a falhar, indicia que algo não está bem e que algo poderá vir a mudar.

A ação decorre entre uma terça-feira e uma quinta-feira. São dias a meio da semana. O fim de semana traria algo fora da rotina, a sexta-feira anteciparia o fim de semana e a segunda-feira ainda teria réstias dos dois dias anteriores. Estamos perante três dias que serão o dia típico desta mulher, viúva, e do seu filho. A rotina e as ações são encaradas como um ritual, para que seja dada uma falsa paz de espírito e se escondam silêncios em que haveria tempo para autorreflexão e consciência do “eu” da protagonista. Mesmo quando Jeanne e Sylvain (Jan Decorte) jantam mais tarde, o segundo sugere que naquela noite não realizem o seu passeio habitual noturno pela cidade. Jeanne concorda. Apesar dessa concordância entre ambos, na sequência seguinte vemo-los a saírem do apartamento. O passeio pela cidade não é realizado por uma razão lúdica, mas sim para manter uma rotina não verbal pré-acordada entre ambos. O facto de não realizarem o passeio significaria uma drástica mudança na rotina dos dois. Embora pareça algo mundano, poderia abrir espaço temporal para a reflexão, que é daquilo que as personagens fogem neste filme. Os seus corpos não são visíveis enquanto passeiam pela cidade, apenas as luzes dos candeeiros e dos carros que passam. Ouvimos os seus passos e não se falam, quase como se não estivessem lá e não vissem aquilo que os rodeia.

Todas as ações que Jeanne faz são puramente mecânicas, com o objetivo de manter uma estrutura que esconde depressão e ansiedade profundas, advindas de uma frustração pessoal de não ter uma motivação maior para viver. Seis anos volvidos da morte do seu marido, Dielman não sai do seu papel social de cuidado, do filho e das tarefas domésticas. Mesmo quando as ações apelam à emoção, como quando a vemos a cuidar duma criança ou a fazer trabalho sexual, os seus gestos e a sua expressão são neutros, no entanto obsessivos por manter sempre os objetos e os espaços organizados e limpos.

A realizadora filma a totalidade das tarefas domésticas e transporta a ansiedade e frustração de Jeanne para os espectadores, que inicialmente se identificam pelo tema mundano, mas numa segunda instância começam a inquietar-se com a duração e repetição dos mesmos. Desta forma, existe uma identificação do espectador com Jeanne, uma vez que partilham o mesmo tipo de emoções após a primeira hora do filme.

O tempo e os espaços são de facto aquilo que move um filme que aparentemente não tem muita ação, mas que nos intriga e conduz a observar todos os detalhes. A começar pelo título, nome e morada de Jeanne, seguidos pelo seu confinamento quase total ao espaço interior — mesmo quando este é exterior — , a obra apresenta-nos sempre os mesmos locais assim como as mesmas ações, algo que é acentuado pela utilização do mesmo ângulo de câmara.

Será também importante fazer notar a importância da utilização do fora de campo em vários momentos do filme. Ao invés da câmara seguir a ação quando ela muda de espaço, permanece imóvel. Desta forma o espectador é incentivado a utilizar o som para descodificar aquilo que decorre no espaço, mas que não vê.

No final do filme surge um clímax algo inesperado que funciona como libertação e resultado da frustração de Jeanne. Observamos que existe um acumular de ações que saem da norma, e um crescimento exponencial da ansiedade de Jeanne nos seus silêncios, expressões e gestos. No entanto, nada nos levaria a pensar que poderia projetar a sua frustração noutra pessoa, uma vez que se demonstra ao longo dos três dias como defensora e praticante do ato de servir o outro, quer seja o seu filho, que nada participa nas tarefas domésticas, os homens que recebe em casa, com os quais tem sexo, ou até a mãe do filho de quem cuida por umas horas, cujos desabafos costuma ouvir.

O filme de Akerman surge numa época em que o masculino predominava na esfera do cinema. Chega-nos aos dias de hoje como uma afirmação feminista sobre o papel da mulher no cinema e na sociedade de 1975, e uma reflexão sobre a autora e a sua história e personalidade.

↓ More Selected Work